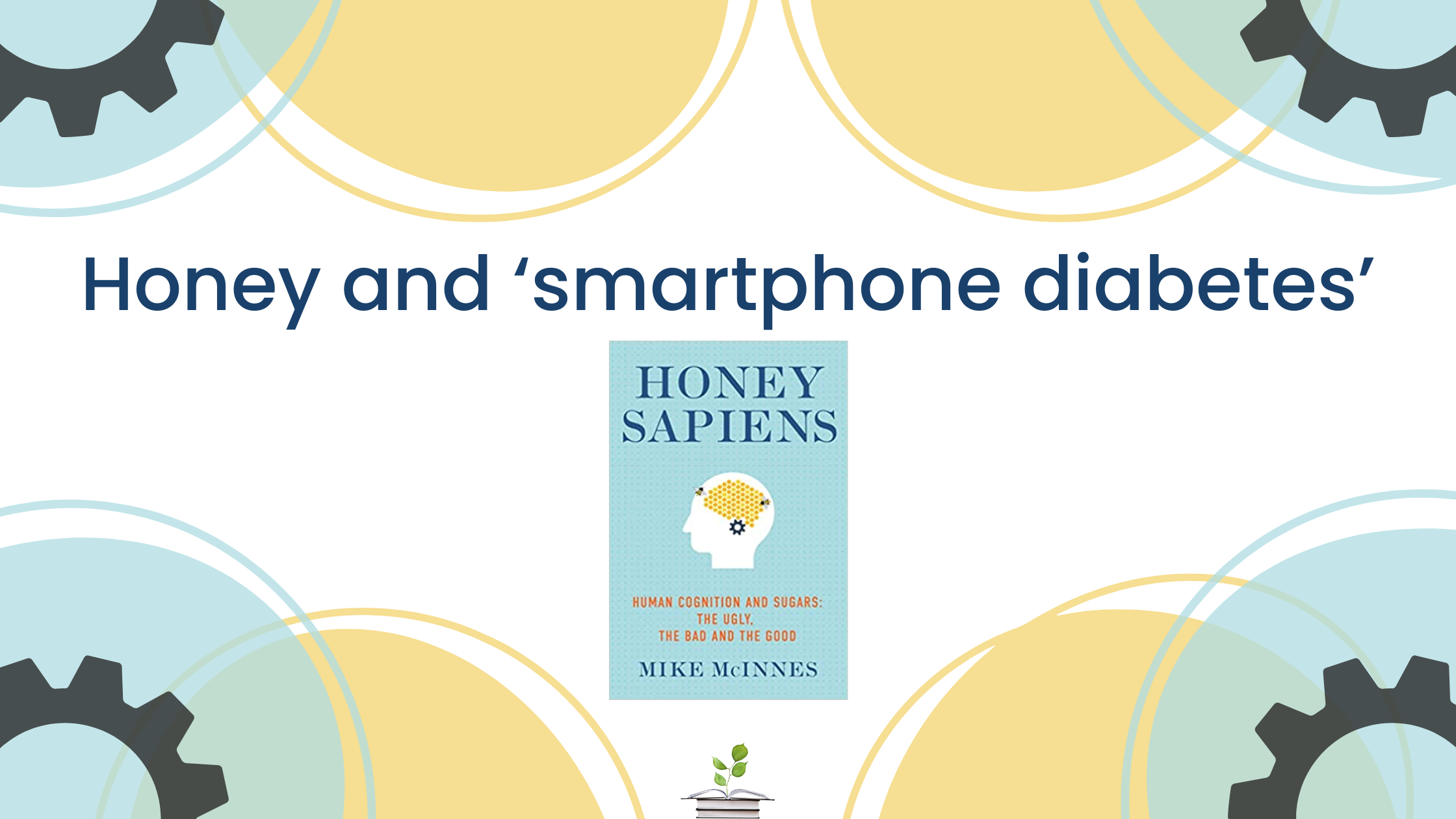

Blog written by Mike McInnes, author of ‘Honey Sapiens’, available soon at Hammersmith Health Books.

It may seem a stretch to suggest that when you order a new smartphone you also purchase a pot of good quality honey from your local beekeeper, but there are sound scientific reasons why this may be justified.

Blue light and neurodegeneration

In the early days of cell phone use, reports in the media raised alarm around the issues of radio frequency and electromagnetic fields causing neurological damage. However, recent concerns have focused on the much more potent effects of chronic exposure to blue-light emissions generated from LED devices, including cell phone, computer and tablet screens. Marie et al in 2018 showed that blue light is the most potent oxidative range witin the visible light spectrum,<1> concentrated multiple times daily onto our retinas by our smart phones for an average of four hours. Cheung et al in 2016 had already shown how this affects the whole metabolism, not just the retina.<2>

Now a new study<3> has confirmed this finding and shown that the effects of blue light are age-dependent – the problems it causes are chronic and differ depending on your stage of life. A young person is vulnerable to blue-light-induced cerebral diabetes.

The Mechanism driving neurodegeneration

A key driver of this damage is oxidation, and thereby suppression, of the enzyme that acts as the brain’s energy pump – glutamine synthetase. Its name may not yet be familiar to you (wait for my forthcoming book Honey Sapiens), but it is ancient (3.8 billion years old<4>) and serves all animate species, including humans. Its healthy functioning is key to our ability to think because without enough energy our brain ceases to function (we go into a coma and die); if it is overwhelmed by energy overload from too much sugar, or by the effects of chronic excess blue light, neurodegeneration will follow.

Is there any way to mitigate this risk other than to avoid all screens – an impossibility for most of us, but particularly for the young whose social lives and education rely so much on technology? How can we provide our children with photo-protection? As you will have guessed from my opening paragraph, the answer is honey.

The amazing protective properties of honey

There is good evidence (Crittenden, 2011) that honey was key to the intellectual leap that took Homo sapiens into being the cognitively advanced species we are now.<5> This is because it contains an amazing range of bioflavonoids that honeybees source from flowering plants – the result of over 100 million years of coevolution.

Honeybees have compound eyes with very sharp vision. They are highly sensitive to blue light, which is vital for foraging success. The bioflavonoids they collect provide them with optimal photo-protection<6> despite the colossal quantities of circulating sugars they live with (up to 50 times that of humans).<7>

If, as is surely the case, we humans continue to increase our use of blue-light information devices, what if anything may we do to protect ourselves from neurological damage? We can learn from the honeybee, reject refined sugars in food and drink in favour of honey, and protect future cognition from photo-neuropathology, via the honey bioflavonoids.<8>

References

-

- 1. Marie M, Bigot K, Angebault C, et al. Light action spectrum on oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage in A2E-loaded retinal pigment epithelium cells. Cell Death Dis 2018; 9(3): 287. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0331-5.

- 2. Cheung IN, Zee PC, Shalman D, et al. Morning and evening blue-enriched light exposure alters metabolic function in normal weight adults. PlosOne 2016; 11(5): e0155601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155601

- 3. Song Y, et al. Age-dependent effects of blue light exposure on lifespan, neurodegeneration, and mitochondria physiology in Drosophila melanogaster. NPJ Aging 2022 Jul 27; 8(1): 11. Doi: 1038/s41514-022-00092-z PMID: 35927421

- 4. Kumada Y, et al. Evolution of the glutamine synthetase gene, one of the oldest existing and functioning genes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 1993 Apr 1; 90(7): 3009-3013. doi: 10.10.1073/pnas.90.7.3009. PMID: 8096645

- 5. Crittenden AN. The Importance of Honey Consumption in Human Evolution. Food and Foodways 2011 Dec 8; 19(4): 257-273. https://doi.org/10.1080/07409710.2011.630618

- 6. Forero AG, et al. Photoprotective and Antigenotoxic Effects of the Flavonoids Apigenin, Naringenin and Pinocembrin. Photochemistry & Photobiology 2019 Jul; 95(4); 1010-1018. DOI: 10.1111/php.13085 PMID: 30636010 (Note: Apigenin, Naringenin and Pinocembrin are three examples of the many flavonoids in honey that are photo-protective.)

- 7. Blatt J, Roces F. Haemolymph Sugar Levels in Foraging Honeybees (Apis Mellifera Carnica): Dependence on Metabolic Rate and in Vivo Measurement of Maximal Rates of Trehalose Synthesis. Journal of Experimental Biology 2001 Aug; 204(Pt 15): 2709-2716. DOI: 10.1242/jeb.204.15.2709. PMID: 11533121.