The enforced closeness of the holiday season can have an all-too-familiar downside. Some of the most wrenching fall-outs among nearest and dearest tend to occur over Christmas and the New Year.

But, before you think about escaping the mandatory get-togethers and making yourself permanently unavailable to family and friends, think about this – they may just be keeping you alive.

This is the opinion of the authors of a paradigm-shifting new book on the importance of closeness and communication to human health and wellbeing. According to Garner Thomson and Khalid Khan, authors of Magic in Practice – Introducing Medical NLP, the Art and Science of Language in Healing and Health, a strong connection with both family and friends is a better predictor of health and longevity than doing all the ‘right’ things, such as quitting smoking, eating your five a day, and getting plenty of sleep.

They point to a landmark study, started in the 1940s, and still the subject of intensive research.

Scientists were intrigued by strikingly low rates of myocardial infarction reported from the little Pennsylvanian town of Roseto, where they expected to find a fit, tobacco- and alcohol-free community enjoying all the benefits of clean-living. When they arrived, they found as many smokers, drinkers and couch potatoes as in the rest of the country, where heart disease was on the rise.

The difference between Roseto and other similar towns, the researchers discovered, was a particularly cohesive social structure.

“The inhabitants of the little town were unique in the experience of the scientists who were drawn there,” says Garner Thomson. “They could be described as ‘barn-raisers’ – which is to say if someone’s barn burned down, everybody in the town turned out to rebuild it. Somehow, the closeness Rosetans enjoyed inoculated them against cardiac and other problems

“Clearly this premise had to be tested – and time was the only true test. The scientists reasoned that if the society changed, became less cohesive and more like its neighbouring towns and cities, the effect would eventually disappear.

“Sadly, as the community became steadily more ‘Americanised’, this proved to be true.”

The 50-year longitudinal study, published in 1992, categorically established that social support and connectedness had provided a powerfully salutogenic (health-promoting) effect on the heart.[1]

Nor was this a random fluctuation affecting a small, isolated community, the authors say.

A number of studies have since confirmed that host resistance to a wide range of illnesses is affected by the social context in which you live and the support you feel you receive. A recent study of 2,264 women diagnosed with breast cancer concluded that those without strong social bonds were up to 61% more likely to die within three years of diagnosis.

According to Dr Candyce Kroenke, lead researcher at the Kaiser Permanente Research Centre, California, the risk of death equals well-established risk factors, including smoking and alcohol consumption, and exceeds the influence of other risk factors such as physical inactivity and obesity.[2]

At least two major studies have suggested that loneliness can double the risk of elderly people developing Alzheimer-like diseases.

“What is particularly interesting about these studies is the suggestion that it is feelings of loneliness, rather than social isolation itself, that may cause the corrosive effects of dementia and other problems,” Thomson says. [3],[4]

Key factors in social integration have been identified as having someone to confide in, help with financial issues and offer practical support, such as baby-sitting, when you need it, and with whom you can discuss problems and share solutions.[5] “These are what we call ‘3 am friends,” says Thomson, “people we can call for support at any hour, no matter how early, and know they will always have time for us.”

So, before you decide to celebrate the holiday season away from Aunty Elsie and Uncle Edward, think very carefully about the possible consequences. Some of the other established benefits of social support and connectedness include: extended lifespan (double that of people with low social ties)[6]; improved recovery from heart attack (three times better for those with high social ties)[7]; reduced progression from HIV to Aids [8] and, even protection from the common cold.[9]

Magic in Practice – Introducing Medical NLP, the Art and Science of Language in Healing and Health is available as paperback or eBook from £6.99. Enter coupon code Xmas15 at checkout for a 15% discount on your basket.

[1] Egolf B, Lasker J, Wolf S, Potvin L (1992) The Roseto effect: a 50-year comparison of mortality rates. American Journal of Public Health 82 (8): 1089–92.

[2] Kaiser Permanente, news release, Nov. 9, 2012.

[3] Wilson RS et.al. (2007) Loneliness and Risk of Alzheimer Disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 64(2): 234-240.

[4][4] Holwerda TJ et al. (2012) Feelings of loneliness, but not social isolation, predict dementia onset: results from the Amsterdam Study of the Elderly (AMSTEL). J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23232034.

[5] Anderson NB, Anderson PE (2003) Emotional Longevity. New York: Viking Penguin.

[6] House JS, Robbins C, Metzner HL (1982) The association of social relationships and activities with mortality: prospective evidence from the Tecumseh Community Health Study. American Journal of Epidemiology 116: 123–40.

[7] Berkman LF, Leo-Summers L, Horwitz RI (1992) Emotional support and survival following myocardial infarction: a prospective, population-based study of the elderly. Annals of Internal Medicine 117: 1003–9.

[8] Leserman J et al (2000) Impact of stressful life events, depression, social support, coping and cortisol. American Journal of Psychiatry 157: 1221–28.

[9] Cohen S et al (1997) Social ties and susceptibility to the common cold. Journal of the American Medical Association 277: 1940–4.

Crudites; colorful peppers, celery, broccoli, cauliflower and cherry tomatoes, served with a dip of plain yogurt with garlic powder, lemon juice, salt, pepper and herbs mixed in.

Crudites; colorful peppers, celery, broccoli, cauliflower and cherry tomatoes, served with a dip of plain yogurt with garlic powder, lemon juice, salt, pepper and herbs mixed in.

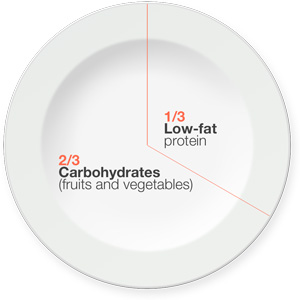

Makes 8, 1-block servings of balanced protein, carbohydrate and fat. Serve warm or cold.

Makes 8, 1-block servings of balanced protein, carbohydrate and fat. Serve warm or cold.